Redactioneel

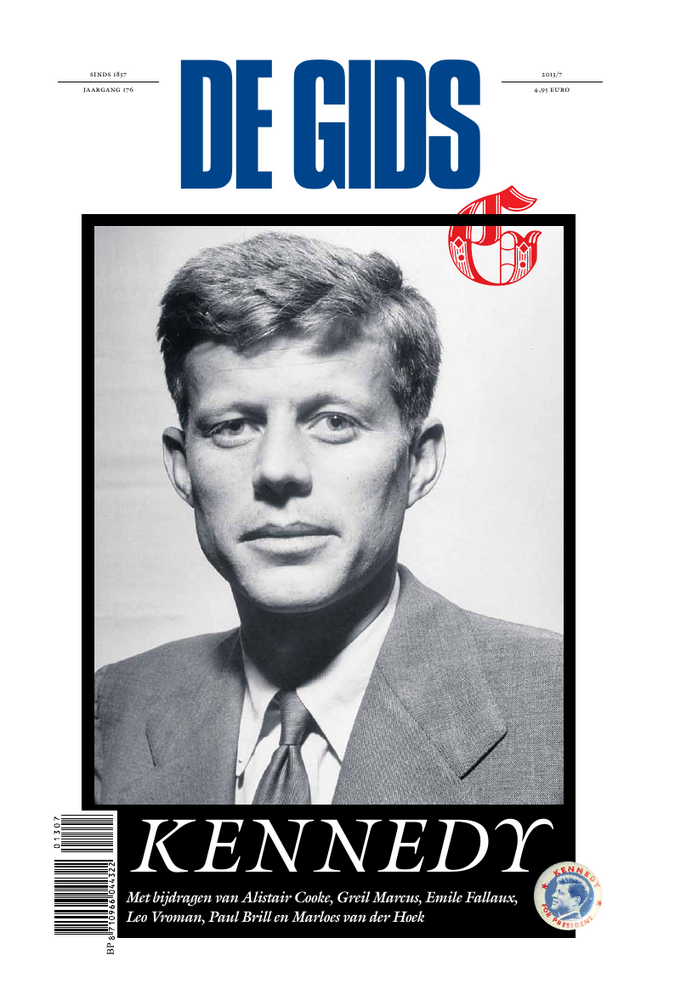

I was raised in a family of California Democrats. I grew up hating Richard Nixon. But John F. Kennedy – everyone referred to him as Jack Kennedy – was thrilling on his own terms, or what seemed to be his own terms. At the age of 15, I worked as hard as I could for his election. I heard him speak at the Cow Palace in San Francisco in the fall, met a girl in the crowd who became a girlfriend, walked precincts and handed out literature. When I saw a painting of him as a tousled, unkempt, let’s-get-down-to-work figure on the cover of Time magazine the week before the election, I took it as a prediction and an endorsement. Somehow the closeness of the election – never mind whether Richard Daley did or didn’t steal Illinois for Kennedy – didn’t register for me. I couldn’t believe he wouldn’t be elected.

But by the fall of 1963, I’d given up on him, because his coldness on civil rights issues – the great national question – was so apparent. I’d somehow missed the cataclysm of the Cuban Missile Crisis, too. There was a phoniness at the heart of Kennedy as president – without any knowledge of the way he’d turned the White House into a brothel, or his fundamental unseriousness as a politician, everything lined out so pitilessly in Gary Wills’s The Kennedy Imprisonment, I could sense that.

His assassination didn’t turn him into a saint for me. Yet it was the most horrendous event I’ve ever lived through, and the consequences have been incalculable. There is no way to enclose the question of what in American life was shattered, and how completely, by his murder. There are countless reasons for this, and to go into them would take volumes and years and even then the question might not even be properly raised, let alone answered.

Compare it to a love affair. One party betrays the other. The betrayer is caught, or confesses, begs forgiveness, foreswears all acts, and is forgiven, or never admits anything and no betrayal is ever proved, but there is a certain absence now present, and on both sides. There is something that can never be regained, even if it’s never spoken of, even if neither party thinks about it. There is a carefulness. It’s a lack of trust in the sense that, crossing the street, you no longer trust that cars will stop for you in the crosswalk. You could be run over at any time, and not by accident.

I have thought, for so many times, about whether the person or persons responsible for the assassination ever thought of the enormous wound, the gaping, bleeding, and invisible sore he or they inflicted on the country, leaving it forever less than it was, no longer convinced, in the most secret places of its heart, that the country was good, or right, if the whole story of American democracy had not been, in some way, a fake. Of course whoever brought this about didn’t care, but that is what it all cost.

The assassination of Bobby Kennedy five years later was more politically disastrous. Lyndon Johnson was a far more effective and committed president than JFK ever thought of being. I have never believed the so-called evidence, let alone arguments, that had Kennedy lived he would have extricated the country from Vietnam, let alone the claims that he was preparing to do so, and that was why the CIA killed him. His mentality was purely Cold War. Who knows what he wouldn’t have done to win the war before his presidency, had he lived, would have been over – in 1968, when everything Johnson had done had led to defeat and disaster, in Vietnam and the US? Lyndon Johnson could admit he failed; I doubt Kennedy could have. Robert F. Kennedy was a confused, inspired, idealistic, conflicted politician, and there is, again, no way of knowing what he might have done as president – in 1972, because even if he had lived Hubert Humphrey already had the presidential nomination locked up and RFK would have been a protest candidate at the 1968 convention, if not the nominee for vice-president. But RKF was himself a wounded, damaged, chastened person by 1968, and because of the same wound the country suffered with JFK’s murder. He no longer believed what he had believed. He no longer had faith that will was efficacy. He had become fatalistic and reckless. I wanted the chance to take a chance on him.

I remember the night of his death in every detail: waiting up all night for the final bad news you knew was coming. I remember it more clearly than I would like to. But psychically, the country recovered from his assassination, even if it didn’t recover politically. As a matter of mind and heart, the country has not recovered from the plain and absolute shock of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, any more than it has ever recovered from the assassination of Lincoln. Both said the same thing: whatever you believed, it was all lies. Lies you told yourself, lies you took from someone else, the country, too. Your own life, your own past, your own future, all those things you flatter yourself are yours at all.

_ * De titel verwijst naar het nummer ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ van de Rolling Stones: ‘I shouted out / “Who killed the Kennedys?” / When after all / It was you and me’._

Assassination of J. F. Kennedy

De internet gids

Brief uit Brooklyn

De ultieme beproeving

Wilde wijnruit

Een ogenblik van zwakte

Poëzie

Op uitnodiging

De internet gids

De stuurloze stad

Het geheugen en de processor

De school

Kroniek & Kritiek

Kameraad De Vries

Essay

Bedrieglijk spel

Shining India, de keerzijde

Democratie, gelijkheid en markt

Denken in tweespraak: van Diderot tot Sloterdijk

Poëzie

Ik zou mij schamen

Poëzie